A Met Parsifal to Remember

I was fortunate to be able to attend the final performance of the long awaited revival of François Girard's production of Wagner's Parsifal at the Metropolitan Opera. Perhaps I should change the word "fortunate" to "blessed." Parsifal is my favorite opera, I've heard and seen it many times, in a number of productions and I have no hesitation in stating Girard's is, hands down, the most perfect, emotionally gripping productions in my experience so far. Everything about it spoke to me in a way that was as much spiritual as it was "theatre." And what gripping theatre it was. Mr. Girard was, of course aided by Wagner's masterpiece, so a lot of the work was already laid out for him. This does nothing to lessen his accomplishment, but, in tandem, Wagner and Girard worked magic on a level that is rare in any opera house, and the Met does itself proud by the production of this union.

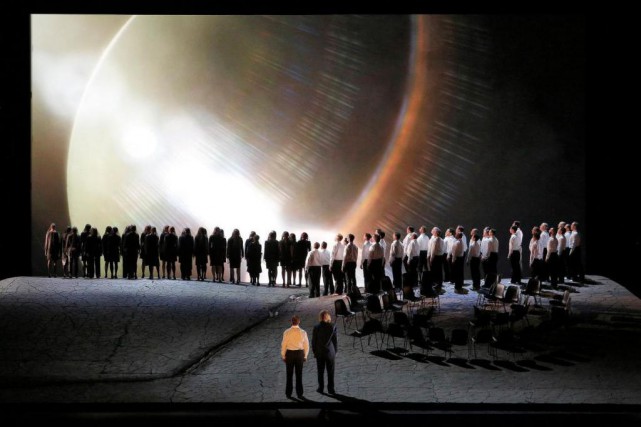

I have watched this production many times in its HD and video format (shout out to Met on Demand, worth its weight in gold) but nothing could quite have prepared me for the effect it had - nor the spell it wove on me - experiencing it in the house. Girard may have updated this to another era, possibly even the future, but he filled it with symbolism, gestures and experiences that felt as ancient as the first humans to walk upright. He explored Wagner's text more thoroughly than any traditional production I've experienced, including our relationship to animals and nature. The stating was complex in what it asked of its participants, far more so than could be gleaned from video; the constant movement, gesticulations, bowing, hand and arm gestures were dazzling, and mysteriously moving in their effect. They were not just "show," but filled with purpose, a history that, even if one could only guess and still not understand (as was my case) added to the sense of awe and wonderment Wagner built in to his libretto and score. There was at times, especially when viewed from the balcony and higher levels, the look of a heavily choreographed musical, not in a cheap, or frilly way, but just beautiful, the concentric circles of the Knights, for example had a "June Taylor Dancers" quality about it that surprised me yet fit perfectly to the staging and story.

The constant changing of backgrounds, shifting with the mood and color of the music was never less than breathtaking, and, while some I know complained about them, I felt only enhanced and heightened what was happening in the pit and onstage.

Musically, things could hardly have been improved upon. Maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the Met orchestra and chorus in a masterful way that belies his experience, the participants responding completely to everything he asked of them. The cast was about as fine an ensemble of singers as has even taken part in a Parsifal, going back to the beginning of anyone alive's memory.

Foremost in that cast was the first voice we hear, Gurnemanz, here in the person of Rene Pape. There have been other beautifully sung Gurnemanz - Salminen, Hines, Moll and Siepi spring to mind - but for me, no singer has approached the text as delicately and as meaningfully as Pape has, particularly in this run. Some say Pape is not a particularly good actor, but I will say, as Gurnemanz, I can't recall a singer getting as "into the skin" of this character as this man has. Every gesture, facial expression, tear and note was of a piece, creating a Gurnemanz of enormous emotional and spiritual wisdom and depth. As opposed to his first Gurnemanz - a true figure of authority - here was a man of great humility and complete service to his order. His phrasing throughout was as delicate and purposeful as a lieder singer. Moments were caressed and uttered with an almost otherworldly beauty, and phrases such as:

"Nun freut sich alle Kreatur

auf des Erlösers holder Spur,

will sein Gebet ihm weihen."

are burned forever into my memory. It was that kind of performance.

Peter Mattei was a surprise the first time he approached Amfortas, a surprise in the very best sense, indeed. With a timbre lighter than we are normally used to hearing in the role, this was a youthful King whose suffering made one pity him in the most honorable sense. Mattei, with that beautiful voice, was capable of making us not only sympathetic to Amfortas, he went so far as to break out hearts and share in that pain. It was nothing short of remarkable. His restoration at the opera's denouement made us feel that the title character's own painful journey, was worth the trip, both to the opera house, and Monsalvat itself.

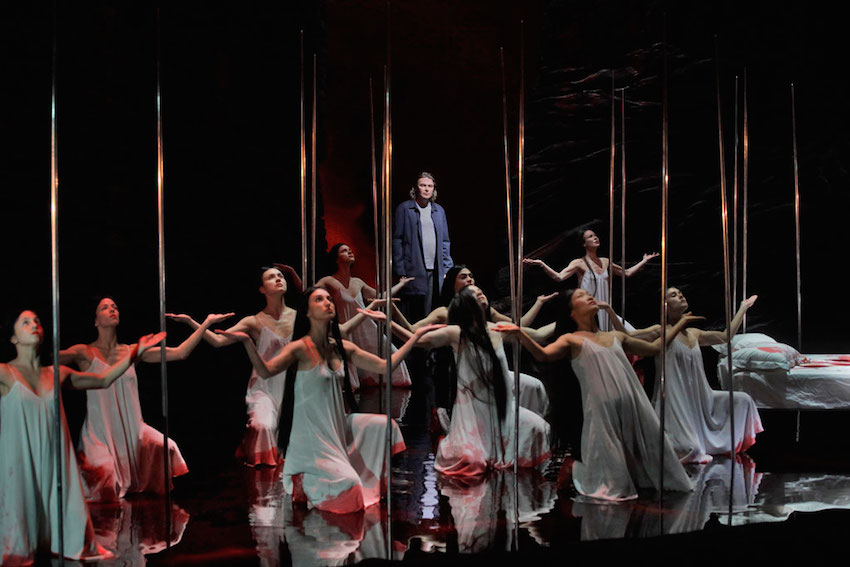

In most performance I have always felt Klingsor was never as deliciously malevolent as Wagner painted him. All that changes in the performance of Evgeny Nikitin. Here was juicy, brutal, unhinged menace, booming of voice and owning his place in the dark realm. There were subtle touches unseen (by me) before, for example, in his short prelude, Nikitin's Klingsor is not only ringing his hands and painting himself with blood, but he mimics some of the gestures of the grail ceremony we'd witnessed in the first act, most notably the kissing of the fingers which previously was passed from brother-to-brother, yet Klinsor has no one to pass this onto. There was a sort of pain, then anger on his face as his hands reached out to . . . no one. The moment was simultaneously telling, touching and chilling.

He was matched in his movements in the brilliantly choreographed movements of the Blumenmädchen who moved as one and made for as spectacular a stage picture as one could hope for. The singing by these "girls" was sensuous and had a youthful femininity that seemed fresh and erotic - both welcome elements. These were not middle aged women in flowing caftans trying to lure a pudgy tenor dressed as a boy, but physically alluring, manipulative menaces using their wiles. It was, in a word; hot.

Evelyn Herlitzius, who made her company debut in this run, presented us with richly drawn, emotionally gripping

Kundry. Bolder and perhaps more wild than many before her both vocally and dramatically she "felt" like Kundry. There was not the beauty of tone of, say, Crespin (who compared in that department?) or Troyanos, and top notes were on pitch, though often lunged at, the effect was special and one just believed this was Kundry.

In the title role we were treated to a much lighter sounding Parsifal than anyone can probably recall . . . certainly in my memory there has been no tenor who made this same effect. The "boyish" timbre of his voice bothered some, but me, not at all. While the voice has a "thin" quality to it, Vogt projects it masterfully, and made me believe every moment. I'd heard criticisms that Parsifal should sound "older" in the final act, but I personally don't buy into that. Most of us have had the same voice quality since we were young, and, as a friend told me (paraphrasing someone), "your voice is your voice, you can't pick up another one up at the corner store" adding, "especially during a second intermission."

As one always hopes for every opera, particularly Parsifal, the audience was about as well behaved as could be, coughing was at a minimum (usually only when dust seemed to blast out of the air conditioning system), no applause before the music was finished, everyone seemed hushed and caught up in the moment. Indeed, at the ovation, everything that had been held in check was given ample opportunity to explode, and that's the correct word for what happened when the curtain rose for bow time. Every singer received sustained applause and cheers, the chorus was roared at as was the incoming Music Director, who, after working so hard for so long, could not contain himself, running to every corner of the stage, hugging and shaking hands with a youthful exuberance that bodes well for the company's future. All things came together in a way that was uniquely special, and I received what I always want from a Parsifal: everything in the world.

Photos by Ken Howard taken from multiple internet sources

Labels: Evelyn Herlitzius, Evgeny Nikitin, Francois Girard, Klaus Vogt, Metropolitan Opera, Parsifal, Peter Mattei, Rene Pape, Wagner, Yannick Nezet-Seguin