Parsifal: Memories of the World Premiere

It is the purpose of this paper to give the impression made by the performance of Parsifal at Baireuth, last summer, in view of certain strictures upon the motive of the drama, and without any attempt at musical criticism. In order to do this, I shall have to run over the leading features of the play, already given in the newspapers. Criticism enough, and of an unfavorable sort, there has been, though I heard none of it in Baireuth, nor ever any from those who had been present at the wonderful festival. Perhaps that was because I happened to meet only disciples of Wagner. I fancy that the professional critics, who did publish depreciating comments upon the new opera, and upon Wagner’s methods in general, felt more inclined to that course after they had escaped from the powerful immediate impression of the performance, from the atmosphere of Baireuth, and begun to reflect upon the responsibilities of the special critics to the world at large, and what in particular was their duty towards the whole Wagner movement, assumption, presumption, or whatever it is called, than they did while they were surrounded by the influences that Wagner had skillfully brought to bear to effect his purpose on them.

* * * *

Of the ending of Act I Dudley wrote:

During the repast of which Amfortas has not partaken, he sinks from his momentary exaltation, the wound in his side opens afresh, and he cries out in agony. Hearing the cry, Parsifal clutches his heart, and seems to share his agony, but otherwise he stands motionless . . . the knights rise . . . slowly depart in the order in which they came. To the last Parsifal gazes in wonder; and when his guide comes to speak to him, he is so dazed that Gurnemanz, losing all patience at his unresponsive stupidity, pushes him out of the door, and spurns him for a fool. The curtains sweep together, and shut us out from the world that had come to seem to us more real than our own.

For a moment we sat in absolute silence, a stillness that had been unbroken during the whole performance. There was not a note of applause, not a sound. The impression was too profound for expression. We felt that we had been in the presence of a great spiritual reality. I have spoken of this as the impression of a scene. Of course it is understood that this would have been all an empty theatrical spectacle but for the music, which raised us to such heights of imagination and vision. For a moment or two, as I saw, the audience sat in silence; many of them were in tears. Then the doors were opened; the light streamed in. We all arose, with no bustle and hardly a word spoken, and went out into the pleasant sunshine.

I recall the first time I read this description, I could feel my heart swelling, recalling my own experiences with the opera, and imagining his.I loved this.

Warner went on with a moving description of the curtain at the end of the second act:

When the act ended, the audience, still under the spell of the music . . . sat, as before, silent for a moment. Then it rose en masse, and turned to the high box in the rear, where, concealed behind his friends, Wagner sat, and hailed him with a long tempest of applause.

Finally, there is the sharing of his overall experience with Parsifal:

I, for one, did not feel that I had assisted at an opera, but rather that I had witnessed some sacred drama, perhaps a modern miracle play. There were many things in the performance that separated it by a whole world from the opera, as it is usually understood. The drama had a noble theme; there was unity of purpose throughout, and unity in the orchestra, the singing, and the scenery. There were no digressions, no personal excursions of singers, exhibiting themselves and their voices, to destroy the illusion.

The orchestra was a part of the story, and not a mere accompaniment. The players never played, the singers never sang, to the audience. There was not a solo, duet, or any concerted piece 'for effect.' No performer came down to the foot-lights and appealed to the audience . . No applause was given, no encores were asked, no singer turned to the spectators. There was no connection or communication between the stage and the audience. Yet I doubt if singers in any opera ever made a more profound impression, or received more real applause. They were satisfied that they were producing the effect intended. And the composer must have been content when he saw the audience so take his design as to pay his creation the homage of rapt appreciation due to a great work of art.

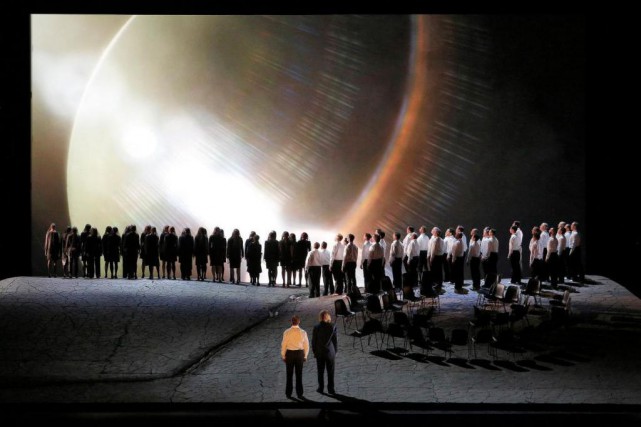

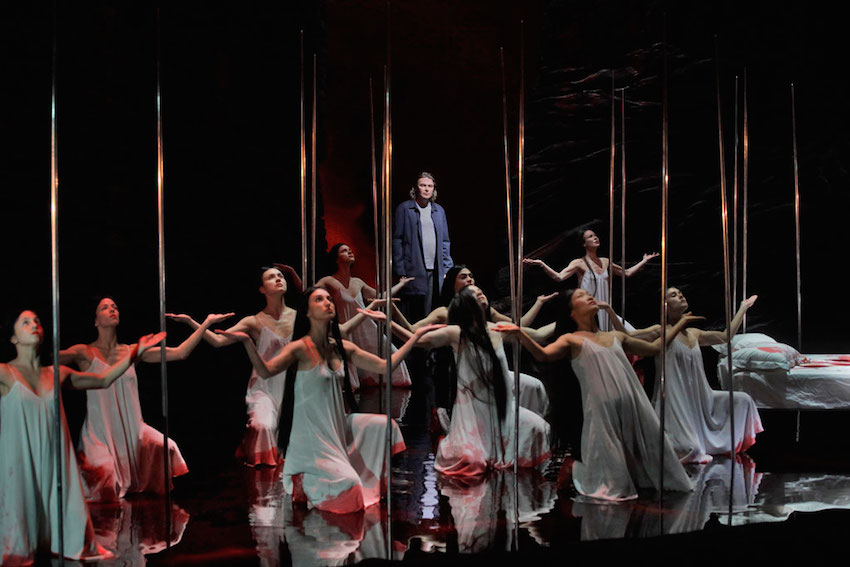

I'm listening to today to a magnificent live performance from the place it all began: Bayreuth. It is under the leadership of Pablo Heras-Casado - who has become a magnificent interpreter and for me approaches the level of Knappertsbusch and his legendary performances from the same house 70+ year ago. Today's cast is one of the best that can be assembled: Andreas Schager (Parsifal), Georg Zeppenfeld (Gurnemanz), Michael Volle (Amfortas), Ekaterina Gubanova (Kundry) and Jordan Shamajam (Klingsor), and Tobias Kehrer. It's almost time for the second act so . . .

Enthüllet den Gral! - Öffnet den Schrein!

Labels: Bayreuth, Charles Dudley Warner, Georg Zeppenfeld, Pablo Heras-Casado, Parsifal, Wagner, World Premiere

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)